How understanding community in rodents can help us understand ourselves

By Anna Bautista

Imagine all of the social interactions you have on a daily basis. We might say goodbye to our partner in the morning and order a coffee from our favorite café with a barista that’s worked there for a few weeks. We might then stand next to strangers on public transportation and arrive at work where we give amicable hellos to our coworkers. And finally, we might end the day with a drink at our favorite sports bar and catch up with a long-time friend before finally heading home, and somehow, we do all of this (most of us) without a hint of hostility. This feature of our species is actually unlike most of the animal kingdom.

Most mice, when introduced to an intruder (analogous to our version of a stranger) will exhibit aggression. And yet, researchers have opted to use mice as the gold standard for research, particularly in biomedical research, for over a hundred years. But how applicable are these animal models, especially when attempting to investigate social relationships?

Deer Fighting during display of intersexual selection. Aggression in the animal kingdom is highly common, especially during the mating season.

Dr. Aubrey Kelly, PhD.

New research at Emory University has attempted to answer this question by establishing a new model species. Aubrey Kelly, associate professor in the department of Psychology, has tried to address this question by asking “how [does] the brain allow individuals to get along with each other?” in a species called African Spiny mice (Acomys dimidiatus). Unlike house mice, spiny mice are communal, meaning that they naturally live in larger groups in the wild. Studying the neural circuitry underlying sociality would be ideal in primates, but Kelly mentions that there simply aren’t a lot of ways to evaluate causal mechanisms in these species. “We obviously can't conduct too many studies with humans because it's unethical to, we can’t manipulate them and take away their friends or force friendships upon them,” she adds.

African Spiny mice (Acomys dimidiatus)

She came to discover these species through a collaborator, Ashley Seifert, professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Kentucky, who studies developmental biology. On a visit to the university, he showed her just how uniquely social these species are. Seifert took a male mouse from one cage and tossed it in another cage. “Among all the species I'd observed before, there would immediately be a brawl, and these guys just didn't care”, says Kelly.

And thus, the spiny mouse colony at Emory was born. Current projects in the lab are investigating social dynamics that occur between and among an established group of individuals. Other projects are exploring the extent to which members of a group participate in parental care, and what implications this may have for future behavioral outcomes of the offspring.

The African spiny mouse colony at Emory University

Since joining the psychology department in 2018, Kelly has made significant contributions to her field, publishing in journals like Current Biology and Nature Scientific Reports. Her track record also holds up. She’s published 22 papers in the past five years, and she received the Frank Beach Early Career award from the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology in 2021. Beyond social neuroscience, the desire to use spiny mice as a model organism has extended to the fields of regenerative biology and reproductive biology. Along with some primates, bats, and elephant shrews, spiny mice can menstruate, and they provide a unique opportunity to explore menstruation dysfunction.

Success for most of us is not without some amount of struggle. When probed on some of her techniques on dealing with the immense workload and balancing it with everyday life, Kelly mentioned that she found it incredibly important to form friendships outside of the sphere of academia when she was a postdoc at Cornell University. So, she engaged in game nights and even techno dancing with her friends Lisa and Rafa. Moreover, she also mentioned that she doesn’t tie her identity towards being an academic. She states, “I identify as being an adventurous person. I identify as somebody who is open-minded. And those things aren't tied to particular places or times.”

My most important learning from Kelly was that we have much more to learn from these little social creatures. We can learn from their biology, it can inform us on our own unique proclivity towards friendly interactions. But perhaps we can also learn about ourselves on a more introspective theme. Taking a note out of Dr. Aubrey Kelly’s book, perhaps our value may be in our sociality. In a world full of rigorous production and consumption, it might benefit us to detach our identity and our self-worth from what we produce and consume, and derive it from the friendships and experiences that enrich our lives.

From curiosity-driven science to real world impacts

Dr. Boghuma Kabisen Titanji, MD, MSc, DTM&H, PhD

By Tehillah T. Chinunga

Dr. Boghuma Kabisen Titanji, MD, MSc, DTM&H, PhD

Dr. Boghuma Kabisen Titanji, MD, MSc, DTM&H, PhD is a formidable presence in the field of medicine and clinical research as a Cameroonian woman scientist at Emory University. Dr. Titanji’s curiosity about science ignited a journey that shaped her future success.

Frequent visits to her father’s lab, a scientist and principal investigator, cultivated her early interest in science. One Sunday afternoon after church, as the routine was on many other weekends, she followed her father who was running errands at his lab. “Please entertain my daughter,” her father said to a PhD student who came to do their share of experiments on the weekend.

Meanwhile, Dr. Titanji’s inquisitive 10-year-old mind was drawn to a container carrying a clear substance, resembling floating “Jell-O”, with holes filled with a red liquid. After waiting for what felt like forever, the PhD student explained to her what a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is, then showed her a picture of the “Jell-O” with bands glowing in the dark. “Amazing!,” she said with wonder. Moments like these were pivotal in capturing her fascination with science. She realized that her consistent academic exposure could not easily be replaced. Her father’s explanations of experiments and hypotheses made science even more fascinating to her.

Photo by Etactics Inc on Unsplash

When asked about hurdles she experienced early in her journey as a woman in science and if she had support or role models to look up to, she responded, “So, while I didn't necessarily have many female role models in science and the challenge of growing up in an environment where it is not necessarily viewed as an asset to be a woman of high academic achievement, my father was very encouraging of his kids to be curious and pursue what they were engaged by, regardless of sex.” Accordingly, Dr. Titanji broke the mold up into adulthood. She did not conform to societal expectations and suggestions of what society thinks should matter for women’s success.

Years later, Dr. Titanji pursued a combined bachelor’s degree and MD degree in Cameroon. After working for two years as a primary care physician, she uncovered her curiosity to merge clinical practice and research. She then pursued a PhD in virology in the UK. Leaving her home country to pursue a graduate degree in the UK came with a cultural shift and navigating people’s biases due to their ignorance of her capabilities. Titanji’s dissertation research focused on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) drug resistance. Afterwards, she returned to clinical practice, specializing in infectious diseases and internal medicine, while also completing a post-doctoral fellowship. Her career goal of combining research and clinical practice was achieved with a faculty position at Emory University.

“Knowing the heavy disease burden of where I come from, I'm still able to feed both parts of my brain with the interactive, patient-centered part, and also carry out research,” said Dr. Titanji.

She currently spends 65 percent of her time on research at Emory University and 35 percent on clinical work at Grady Memorial Hospital and Emory University Hospital. Her research aims to understand how HIV infections lead to injuries to the inner walls of blood vessels, as a result of going through its life cycle, and cause heart problems in people living with HIV.

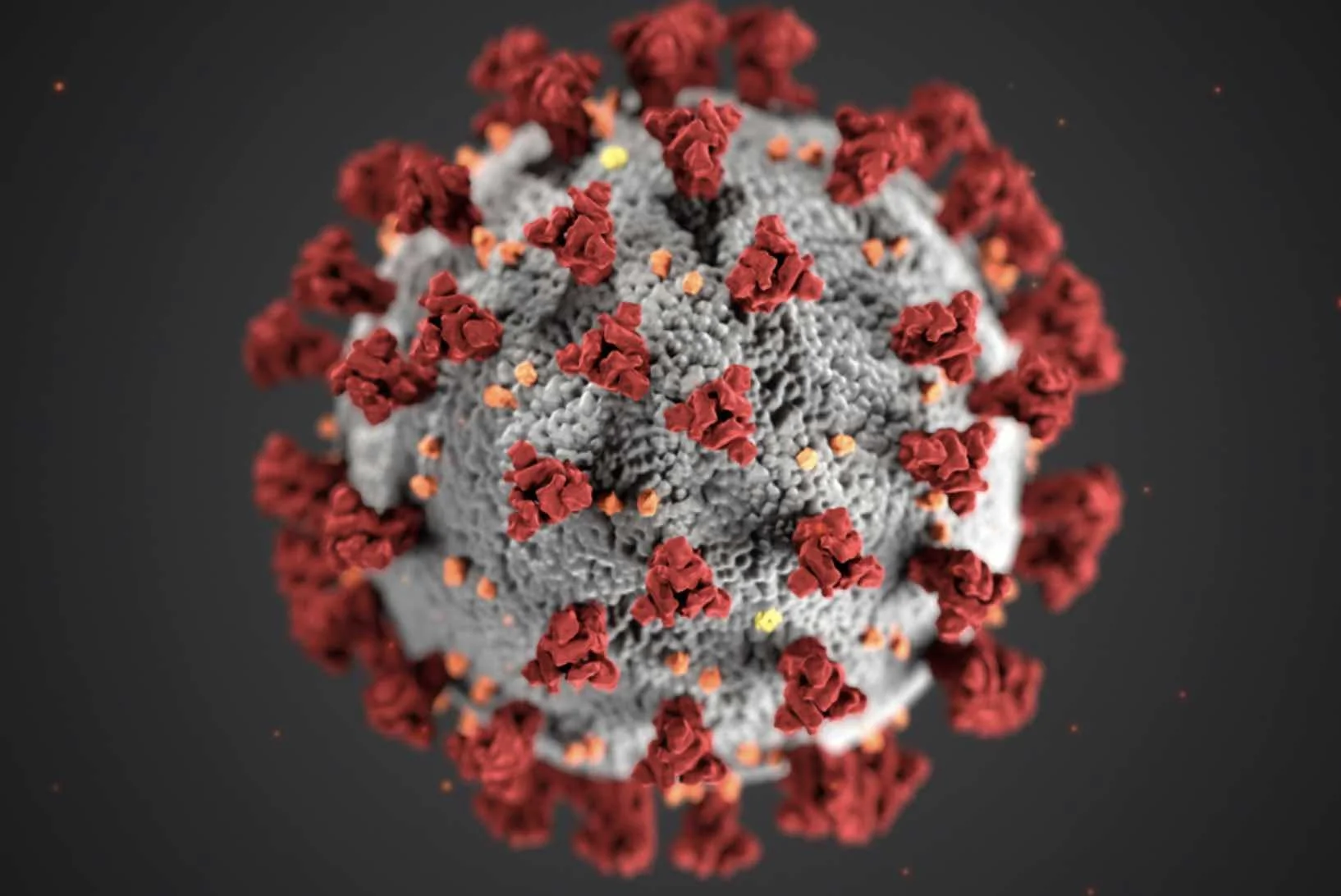

Her excellence and dedication have not gone unnoticed. Among many other accolades, in 2023 Dr. Titanji received the Health Care Heroes award in the Innovator/Researcher Category for her work at the Atlanta VA Medical Center. Dr. Titanji led clinical studies that resulted in baricitinib, an immune modulator and Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitor, being taken into clinical trials to treat coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Cancer cells or infections can hijack chemical reactions in the body. In turn, such abnormalities enable uncontrolled responses by the immune system. That is where JAK inhibitors come in, to restore the body’s control and reduce fatalities. Notably, her Emory-based collaborators and inventors of baricitinib include Raymond Schinazi PhD, DSc and Christina Gavegnano PhD, who did preliminary clinical work which demonstrated antiviral activity against a wide range of viruses.

Dr. Titanji also engages in science communication and advocacy, aiming to influence policy and public health, especially in Africa. In addition to giving a TED talk on Ethical Riddles in HIV Research, while in London, she organized a global health talk series to inform the public and combat health misinformation about the 2014 Ebola outbreak. She emphasized the importance of science communication and advocacy during public health crises. Her global health campaign efforts led to recognition among the BBC 100 Women 2014. More recently, as she actively continues her role as global health advocate, Dr. Titanji was featured on the Global Health Unfiltered podcast in 2024 sharing her thoughts on Uncovering the root causes of the mpox outbreak.

When Dr. Titanji is not at the bench or attending to her patients, she still finds ways to combine science with her personal interests such as cooking and gardening.

Finally, an important reminder for innovative scientists, in Dr. Titanji's words is, “the science you do can be as amazing as you want it to be, but if you are not able to communicate it or use it to drive policy changes that directly impact people's lives, then it's just science out of curiosity.”

Advocating for reproductive rights, one patient at a time

Dr. Tiffany Hailstorks, MD, MPH

Written by Ananya Dash

Dr. Tiffany Hailstorks, MD, MPH

Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022 ending the constitutional right to abortion. Dr. Tiffany Hailstorks, MD, MPH, Director of Division of Complex Family Planning and an associate professor in the department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Emory University School of Medicine, has been adjusting to this reality even before this monumental decision. This is because an anti-abortion law was passed in the U.S. state of Georgia in 2019. The law prevents physicians from performing abortions beyond six weeks, except in special circumstances. She and her fellow physicians have been facing the changes in the legislation for a long time.

“I am surrounded by a group of people whose mission is to provide the best care for our patients, so we rally together to support each other to be able to do that,” says Dr. Hailstorks.

She has an uncanny knack to be optimistic. Nothing, whether it’s changing laws and restrictions, the draining night shifts, or visiting different clinics almost every day, deters her motivations. Ups and downs and the variety in timing and workplaces bring her perspective; she loves her practice.

Dr. Hailstorks always knew that she wanted to pursue medicine. But her path to medicine was slightly unconventional. She majored in chemistry, a rather uncommon major for medical aspirants, in undergraduate. Dr. Hailstorks attributes her early interests in science, especially chemistry, to her high-school chemistry teacher. Despite the hard subject matter, her teacher’s patience and extraordinary teaching abilities led Dr. Hailstorks to enjoy chemistry to the fullest. She even considered applying for an MD/PhD dual degree program until the clinical aspects of medicine drew her in to get an MD.

Dr. Hailstorks went to medical school at Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tennessee, where her love affair with OB/GYN (Obstetrics and Gynecology) procedures began. She reminisces about being in the labor and delivery room for the first time during her clinical rotations. When it was time for her to leave, she was surprised by how fast the day went by. “Is it time for me to go already?” she asked her supervisor with the hope to stay longer for the rotation. This experience was a stepping stone for what a career in OB/GYN could offer to her.

After finishing medical school, Dr. Hailstorks completed her residency in OB/GYN at Howard University Hospital, Washington, DC. Then she moved to Emory University to finish a fellowship in complex family planning– a subspecialization in abortion and contraception. Each of these stages came with their unique challenges. But, she found a supportive environment with her fellow residents to keep growing in her career. She also had a number of female physicians as her mentors who served as role models. “They [mentors] helped me see and hear about their paths in science, how they have navigated medicine, and leadership roles within medicine as women,” says Dr. Hailstorks.

After completing her fellowship, Dr. Hailstorks stayed at Emory University where she is the director of the Division of Complex Family Planning since 2024. She continues to build camaraderie between colleagues in the division that she was welcomed into several years ago. Her work has been recognized through several awards by the Emory University and Castle Connolly, a healthcare research company that recognizes exceptional physicians in the U.S.

Dr. Hailstorks and I chatted about one of them: the Berky Dolores Abreu Spirit Award. She received this award in 2019 in recognition for her extraordinary dedication to foster growth among students, faculty and departments at Emory University from the Centre for Women. “I felt seen by my colleagues,” says Dr. Hailstorks. “I have always encouraged my peers that we are a team and if certain things are challenging, lean in on your team and ask for help. So, I think that the award showed that people were paying attention to me.”

The ripple effects of Dr. Hailstorks’s practice goes beyond Emory. Apart from attending at different Emory clinics, she attends to patients at Grady memorial Hospital and Feminist Women’s Health Centre, a reproductive justice organization. She gets to meet patients who might be uninsured or underinsured at these places. “Being able to provide that type of care for our patients is really important to me,” says Dr. Hailstorks.

Dr. Hailstorks’s exceptional work as a clinician now allows her to wear a number of professional hats. She works with two more reproductive justice-focused non-profit organizations, Sister Love and Sister Song, as a consultant on research projects. Emory-based researchers collaborate with her to run projects focused on abortion care. She also runs industry-sponsored studies to improve and test new contraceptive technologies through randomized trials.

Despite having such a multifaceted career, her most influential contributions are the advocacy work she does for her patients since the passage of anti-abortion legislation in Georgia in 2019. “We created fact sheets so that when our legislators go into different sessions, they have accurate facts about how abortion restrictions impact patient’s day to day care,” Dr. Hailstorks says.

Even in her own practice, she encounters multiple hindrances to exercise the full scope of care that is safe and effective due to laws and restrictions. Even in the face of these challenges, she and others on her team have been able to provide patients the care they need by creating different policies and practices all while maintaining the law. Dr. Hailstorks hopes that patients leave it to their OB/GYNs to decide the best course of action. She wants patients to come to clinics to consult regarding every step of their pregnancy and not be afraid.

When asked about the future of reproductive care, she says that she is hopeful and does the best she can, under the given circumstances. “A lot of people who have been doing advocacy and activism know that it can take a long time to see big leaps or small changes.”

Her words embody optimism for the future of reproductive health but also to each of us as we face obstacles in life. “We must find different paths to be able to continue to push forward.”